The following annotated list contains all 113+ species that have been detected in the hotspot during the summer months of June and July, excluding those such as Swainson’s Thrush or Red-breasted Nuthatch that are late and/or early migrants and clearly do not and have never bred in Plummer’s Hollow.

By the numbers

- Total breeding species since 1972: 92

- Annual breeders: 77

- Regular breeders (not every year): 10

- Bred in the past only: 5

- Summer visitors from nearby populations, may have bred occasionally: ~5

- Summer visitors, unlikely to breed: ~16

Annual breeders are those that have nested in the hotspot every year since 2015 and in many cases for innumerable years prior. Number ranges given are the estimated average lower and upper limits of breeding pairs (not successful nests). The number of breeding pairs for most species fluctuates from year to year, sometimes widely (American Goldfinch, Cedar Waxwing, Chipping Sparrow). The “<5” category includes numerous species that may only have a single nest in the hotspot in any given year. The estimated numbers are derived from June surveys in adequate habitat, extrapolated to all available similar habitat in the hotspot, and are relatively well-refined estimates.

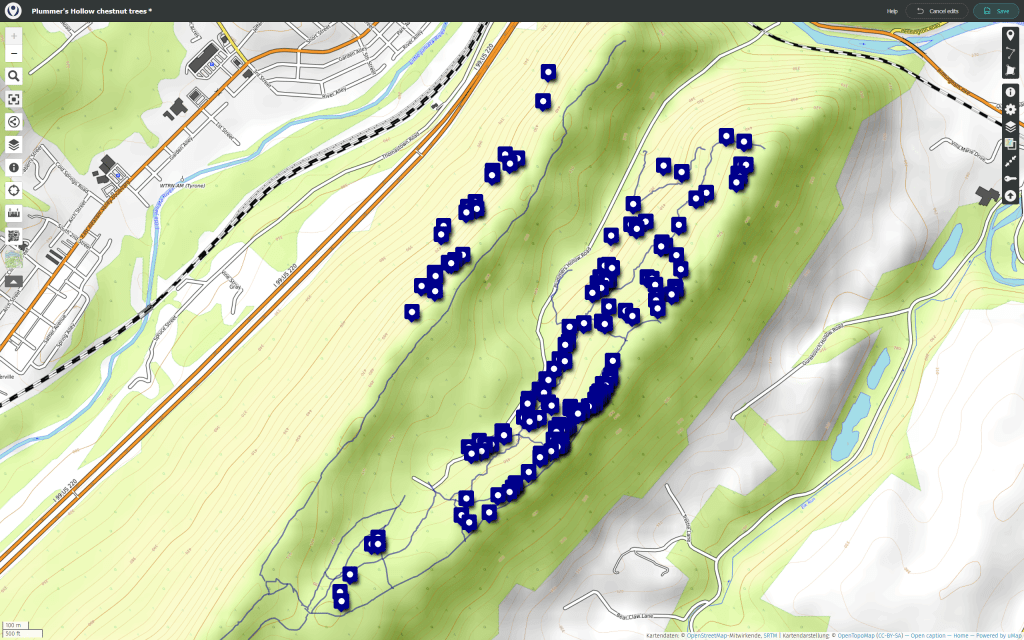

Note: the area of the hotspot is around 700 acres, 600 of which are forest.

Regular breeders, always with less than five pairs in any given year, and sometimes with no breeding pairs, are species that do not breed in the hotspot every year. They may breed in the hotspot only in years when overall populations are high in the area or may be species with other special conditions such as steeply declining populations (Ruffed Grouse) or little appropriate habitat (Wood Duck).

Occasional and former breeders include species such as Kentucky Warbler, Least Flycatcher, Golden-winged Warbler, Yellow-breasted Chat, and American Kestrel that have seen overall species or population numbers decline and/or the disappearance of adequate habitats or niches. Some species, such as Barn Swallow and Rock Pigeon, formerly bred in the barn in the 1980s and before, when domestic animals were present, but have long since abandoned the property, though they breed elsewhere in the hotspot.

Summer visitors fall into two categories:

1) those such as Killdeer, Bald Eagle, and Purple Martin that do not breed in the hotspot but that breed nearby (or once did, in the case of species such as the Common Nighthawk)

2) those that breed nearby and may also breed or have bred undetected in the hotspot (Turkey Vulture)

Habitat notes

The LJR corridor is the riparian corridor formed by the Little Juniata River that is the northern boundary of the hotspot. It contains several species that breed nowhere else in the hotspot, such as Warbling Vireos, swallows, and most aquatic species.

Because the northwest corner (NW corner) contains a small, built-up area of Tyrone in a riparian zone at the confluence of the LJR and Bald Eagle Creek, it also includes species such as House Sparrow, European Starling, Rock Pigeon, House Finch, and Chimney Swift. The LJR corridor also contains the bulk of breeding Baltimore Orioles, Common Grackles, and several other species that nest only sparsely throughout the rest of the hotspot.

Other special breeding zones in the hotspot include the Hollow formed by Plummer’s Hollow run and its tributaries, the high fields, and the Norway spruce grove.

The Hollow is the main area in the hotspot for Louisiana Waterthrush, Acadian Flycatcher, and along with the spruce grove, Blackburnian Warbler. It is also a zone of high concentration for species of concern such as Worm-eating Warbler and Wood Thrush, and the Plummer’s Hollow Run is critically important as a sheltered and clean water source throughout the breeding season.

The spruce grove, originally planted in the 1970s, is the only area of continuous conifer cover in the hotspot. It hosts breeding Chipping Sparrow, Blackburnian Warbler, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Barred Owl, and Sharp-shinned Hawk, often in the same year.

The high fields and adjacent grounds and edges contain common breeding field species such as Field Sparrow, Common Yellowthroat, Indigo Bunting, and Song Sparrow (in marshier areas), but since the demise of chats and Golden-winged Warblers, they do not host any rarer breeders. The common field nesters (particularly in high population years such as 2024), also nest widely in more open parts of the woods (Indigo Bunting), along the powerline right-of-way, along the grassy fringe of the hotspot that borders I-99, and along the LJR corridor and railroad tracks.

The edges of Sinking Valley are home to nesters such as Northern Mockingbird and Eastern Meadowlark that as a result are audibly detectable at dawn in summer from the top of Laurel Ridge. The hotspot’s proximity to large expanses of open fields also results in regular visits from species such as Purple Martin (which hunts over the mountain well before dawn) and occasional visits from others.

Waterfowl

- Canada Goose. Annual breeder, <5, LJR corridor only

- Wood Duck. Regular breeder, <5, scattered locations

- Mallard. Annual breeder, <5, LJR corridor only

- Common Merganser. Likely annual breeder, <5, LJR corridor only, #s increasing

Grouse, Quail, and Allies

- Wild Turkey. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods

- Ruffed Grouse. Regular breeder, <5, deep woods and thickets, pops. crashed in 2000s

Pigeons & Doves

- Rock Pigeon. Annual breeder, NW corner buildings only, 10–25, formerly bred on grounds (1970s)

- Mourning Dove. Annual breeder, 10–25, woods throughout

Cuckoos

- Yellow-billed Cuckoo. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods

- Black-billed Cuckoo. Annual breeder, 5-10, deep woods

Nightjars

- Common Nighthawk. Former summer visitor from breeding populations in Logan Valley (as recently as 1996)

- Eastern Whip-poor-will. Annual breeder, 5–10, deep woods

Swifts & Hummingbirds

- Chimney Swift. Annual breeder, 5–25, mostly NW corner chimneys

- Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Annual breeder, 10–25, woods throughout

Shorebirds & Gulls

- Killdeer. Regular summer visitor, 5+ breeding pairs within 2km of PH

- American Woodcock. Regular breeder, <5, forest edge

- Ring-billed Gull. Occasional summer visitor from breeding populations

Herons

- Green Heron. Likely breeder, <5, LJR corridor only; summer visitor (flyover) from local populations within 5km

- Great Blue Heron. Regular summer visitor, <5 breeding pairs likely within 10km of PH

Vultures, Hawks, & Allies

- Black Vulture. Annual summer visitor, likely breeder, <5 pairs, within 10km of PH

- Turkey Vulture. Annual summer visitor, likely occasional breeder in PH, 25+ breeding pairs within 5km of PH

- Osprey. Annual summer visitor, 1+ breeding pair likely within 20 km of PH

- Sharp-shinned Hawk. Annual breeder, <5, spruce grove and other locations

- Cooper’s Hawk. Annual breeder, <5, deep woods

- Bald Eagle. Annual summer visitor, 2+ nests within 10 km of PH

- Red-shouldered Hawk. Regular summer visitor, likely breeder in nearby riparian zones in valleys

- Broad-winged Hawk. Regular breeder, <5, deep woods

- Red-tailed Hawk. <5. Regular breeder in or near PH.

Owls

- Eastern Screech-Owl. Annual breeder, <5, woods throughout

- Great Horned Owl. Annual breeder, <5, deep woods

- Barred Owl. Annual breeder, <5, spruce grove and deep woods only

Kingfisher & Woodpeckers

- Belted Kingfisher. Likely occasional breeder, LJR corridor only

- Red-bellied Woodpecker. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods throughout

- Downy Woodpecker. Annual breeder, 25–50, woods throughout

- Hairy Woodpecker. Annual breeder, 5–10, deep woods throughout

- Pileated Woodpecker. Annual breeder, <5, deep woods throughout

- Northern Flicker. Annual breeder, <5, woods throughout

Falcons

- American Kestrel. Formerly bred in field, <5, currently a summer visitor. Last nested 2004.

- Merlin. Occasional summer visitor

Tyrant-Flycatchers

- Eastern Wood-Pewee. Annual breeder, 25–50, deep woods throughout

- Acadian Flycatcher. Annual breeder, 10–25, riparian zones in hollows

- Least Flycatcher. Former breeder, <5. As late as 2003, deep woods

- Eastern Phoebe. Annual breeder, 5–10, throughout

- Great Crested Flycatcher. Annual breeder, 5–25, deep woods

- Eastern Kingbird. Occasional summer visitor from breeding pops. in valleys

Vireos

- Yellow-throated Vireo. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods throughout, #s increasing

- Blue-headed Vireo. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods throughout

- Warbling Vireo. Annual breeder, <5, LJR corridor only

- Red-eyed Vireo. Annual breeder, >100, woods throughout

Corvids

- Blue Jay. Annual breeder, 10–25, woods throughout

- American Crow. Annual breeder, 5–10, woods throughout

- Fish Crow. Annual breeder, NW corner only, <5, since 2010s only

- Common Raven. Annual breeder, <5, deep woods

Tits

- Black-capped Chickadee. Annual breeder, 25–50, woods throughout

- Tufted Titmouse. Annual breeder, 25–50, woods throughout

Martins & Swallows

- Tree Swallow. Regular breeder, <5, mostly LJR corridor, bred in field boxes in late 1990s

- Purple Martin. Summer visitor from Sinking Valley populations

- Northern Rough-winged Swallow. Annual breeder, 5–10, LJR corridor only

- Barn Swallow. Annual breeder, 5–10, LJR corridor only, formerly bred on grounds (into 1990s)

- Cliff Swallow. Regular breeder, <5, LJR corridor only

Kinglets, Nuthatches, Treecreepers, & Gnatcatchers

- Golden-crowned Kinglet. Annual breeder, <5, spruce grove

- White-breasted Nuthatch. Annual breeder, 25–50, woods throughout

- Brown Creeper. Occasional summer visitor and possibly breeds occasionally in PH (June 27, 1996, singing and foraging)

- Blue-gray Gnatcatcher. Annual breeder, 10–25, woods throughout

Wrens

- House Wren. Annual breeder, <5, fields/edges

- Winter Wren. Regular to occasional breeder along PH Run, <5. Has never been fully confirmed

- Carolina Wren. Annual breeder, 10–25, throughout

Starlings and Mimids

- European Starling. Annual breeder, 25–50, mostly NW corner buildings

- Gray Catbird. Annual breeder, 25–50, throughout

- Brown Thrasher. Annual breeder, 5–10, scattered brushy locations

- Northern Mockingbird. Occasional summer visitor, breeds in nearby valleys

Thrushes

- Eastern Bluebird. Annual to regular breeder, <5, appears limited to boxes in field

- Veery. Regular summer visitor (often as night flyover) from breeding populations on nearby higher mountains. Singing bird observed June 21, 1993

- Hermit Thrush. Possible occasional or regular breeder; scattering of June and July reports that may pertain to individuals dispersing from breeding areas with 20km.

- Wood Thrush. Annual breeder, 50–100, deep woods and LJR corridor

- American Robin. Annual breeder, 50–100, throughout but most highly concentrated in LJR corridor and NW corner

Waxwings

- Cedar Waxwing. Annual breeder, 10–50, woods throughout

Old World Sparrows

- House Sparrow. Annual breeder, NW corner only, 10–25

Finches

- House Finch. Annual breeder, 10–25, mostly NW corner, scattered elsewhere

- American Goldfinch. Annual breeder, 10–25, throughout

New World Sparrows

- Grasshopper Sparrow. Summer visitor, flyover (moving from disturbed habitats in fields elsewhere)

- Chipping Sparrow. Annual breeder, 10–25, mostly grounds, spruce grove, LJR corridor

- Field Sparrow. Annual breeder, 25–50, fields throughout

- Song Sparrow. Annual breeder, 10–25, fields and riparian areas throughout

- Eastern Towhee. Annual breeder, 50–100, throughout

Yellow-breasted Chat. Annual breeder through 1996, fields and powerline right-of-way; failed breeding attempt in 2024

Blackbirds

- Eastern Meadowlark. Nests in surrounding valleys and can be detected from PH in breeding season

- Orchard Oriole. Possibly regular breeder, pair through breeding season 2023, LJR corridor

- Baltimore Oriole. Annual breeder, 10–25, largest pop. in LJR corridor

- Red-winged Blackbird. Annual breeder, <5, LJR corridor only. Bred in mt fields into early 1980s

- Brown-headed Cowbird. Annual breeder, 10–50

- Common Grackle. Annual breeder, 50–100, primarily LJR corrdor

Wood-Warblers

- Ovenbird. Annual breeder, 50–100, deep woods on mt

- Worm-eating Warbler. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods on mt

- Louisiana Waterthrush. Annual breeder, 10–25, streams and LJR corridor

- Golden-winged Warbler. Bred along field edge into early 2000s (<5)

- Blue-winged Warbler. Possibly bred in the past (found 3 times in early June in 2000s)

- Black-and-white Warbler. Annual breeder, 10–25

- Kentucky Warbler. Occasional breeder, <5, deep woods on mt, bred most recently 2019 (2+ pairs)

- Common Yellowthroat. Annual breeder, 25–50

- Hooded Warbler. Annual breeder, 25–50, deep woods on mt and LJR corridor

- American Redstart. Annual breeder, 25–50, deep woods on mt and LJR corridor

- Cerulean Warbler. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods on mt

- Northern Parula. Annual breeder, <5, deep woods on mt

- Blackburnian Warbler. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods on mt

- Yellow Warbler. Annual breeder, <5, LJR corridor only

- Chestnut-sided Warbler. Bred regularly into the late 1990s

- Black-throated Blue Warbler. Annual breeder, <5, deep woods on mt

- Black-throated Green Warbler. Annual breeder, 10–25, deep woods on mt

Cardinals, Grosbeaks, and Allies

- Scarlet Tanager. Annual breeder, 50–100, deep woods on mt and LJR corridor

- Northern Cardinal. Annual breeder, 25–50, woods and field edges throughout

- Rose-breasted Grosbeak. Annual breeder, 25–50, deep woods on mt and LJR corridor

- Indigo Bunting. Annual breeder, 25–50, woods and field edges throughout