One hundred and fifty-two. That’s how many American chestnuts I was able to locate this autumn on our square mile of mountaintop land, after extensive wandering about the oak-heath forest on Laurel Ridge, their main stronghold, as well as the northwest-facing slope of Sapsucker Ridge, where a smaller scattering remains. I initially tagged each tree, sprout, or (in one or two possible cases) seedling with yellow surveyor’s ribbon, then came back after all the leaves were down to record a bit of data about each one: diameter at breast height, estimated height of tree, whether it’s on the way out, and if so, whether it has any basal sprouts poised to take over.

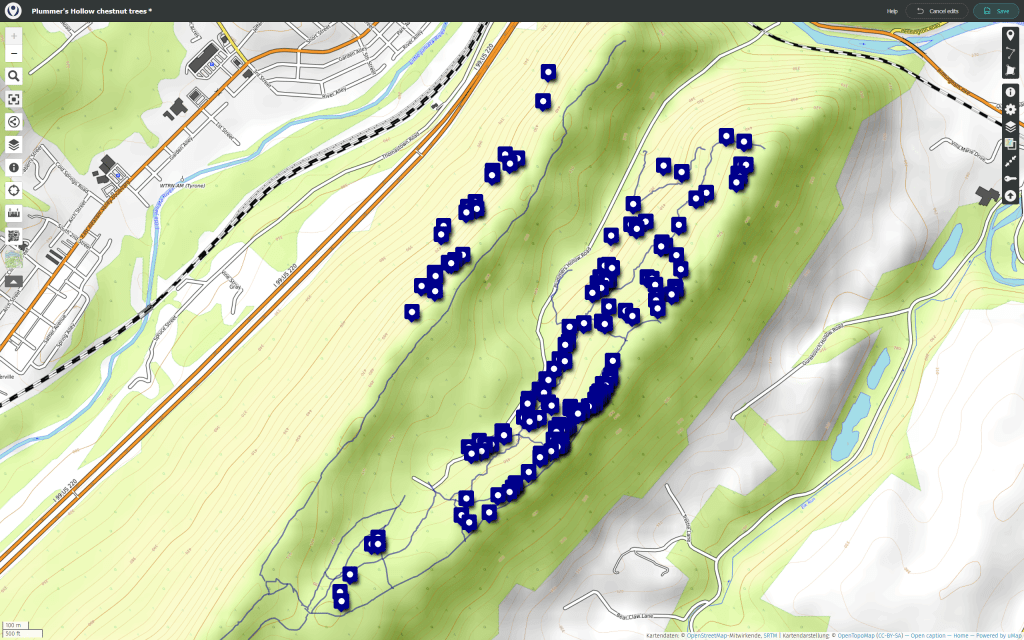

At present I’m using a free app on my phone, Avenza Maps, to record the data. A friend of Eric’s from the American Chestnut Foundation is interested in doing some genetic analysis, and we’ll see what comes from that. It’s possible that a few might actually be Castanea pumila — Allegheny chinquapin or dwarf chestnut, which is also affected by the blight. Many of them are quite tall, however, so I’m assuming that the vast majority are Castanea dentata, though they do also hybridize.

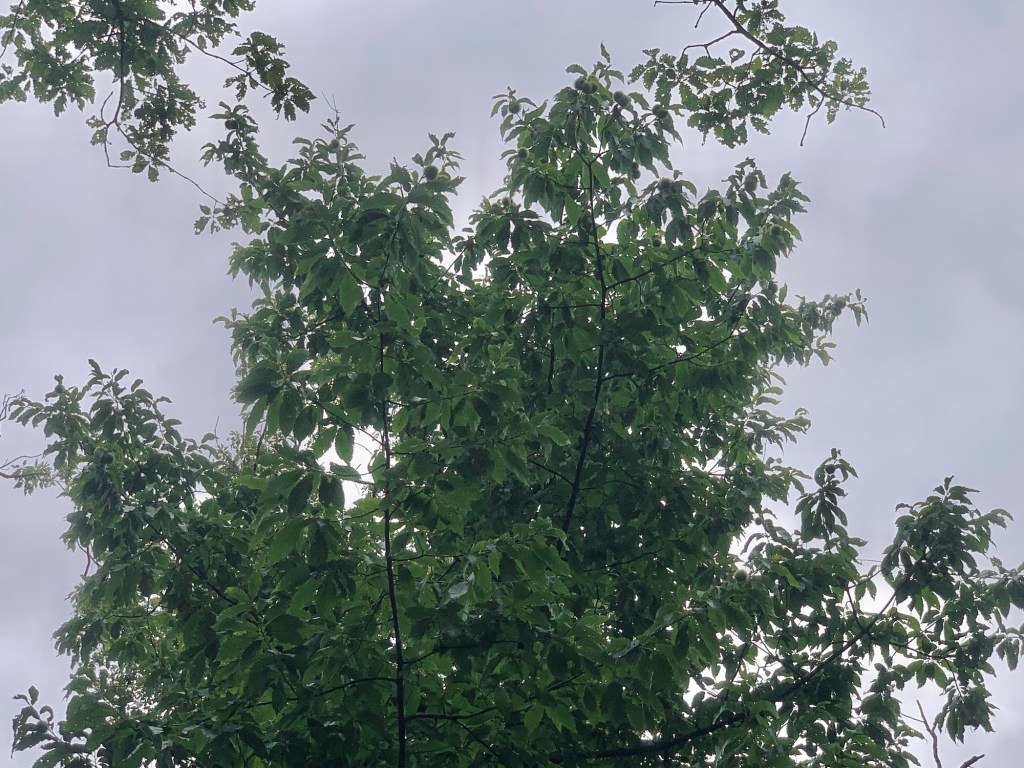

The biggest American chestnut on our end of the mountain is just over the line with a neighbor, and was the only one to bear nuts this year. It came in at 8.7 inches dbh (diameter at breast height, which is standardized at 4.5 feet) and is about 75 feet tall—canopy height where it’s growing. The largest on our own property is 8.4″ dbh and about 70 feet tall, just north of the ridge crest near the end of Laurel Ridge. In second place is one conveniently located adjacent to Laurel Ridge Trail: 7.9″ dbh, ~75 feet tall. Three more are over six inches in diameter, seven more are over five inches, 19 more are over four inches, 35 over 3 inches, and all the rest (80+) smaller than that. I took note of which ones were nearly dead with just one or two, badly deer-browsed sprouts: those will be candidates for deer fencing.

I’m sorry I didn’t start keeping records years ago, but better late than never. I just felt the need to better understand what trees (of various species) we have and how they’re doing in this time of fluctuating deer populations and new invasive species, pests and blights. It’s been heartbreaking to see the nemotode-caused beech leaf disease come into the hollow, bringing the very real possibility that all our lovely old American beeches will die, just as our white ashes have all been killed by the emerald ash borer, the butternut trees have all succumbed to butternut canker, and the wooly adelgid continues its slow decimation of the eastern hemlocks.

The spongy moth (formerly Gypsy moth), though controlled a bit by a virus and fungus now, can still do considerable damage to oaks, especially in combination with late freezes, which are a lot more common in recent years due to global weirding. This is however good news for some of the chestnuts, since canopy openings due to dead oaks may allow more Castanea trees to flower, ennabling cross-fertilization by their insect pollinators, and thereby maybe someday allowing the species to evolve resistance to the blight.

And that’s our primary management goal for chestnuts: to give them the maximum opportunity to evolve resistance—the work of centuries, most likely. So it seemed imperative to start keeping track of them, see whether their numbers are increasing, declining, or remaining about the same, and keep an eye out for possible new sprouts from the nuts these hoary old warriors are still able to produce, once in a while.

I’m not entirely sure where this project goes from here. If anyone has any thoughts or suggestions, leave a comment or otherwise get in touch. As a poet with dyscalculia, I’m not necessarily cut out for doing science, but I do love a good excuse to wander around in the woods, so I’m definitely planning more surveys of some of the rarer trees and shrubs, and possibly other landscape features such as old charcoal hearths. Mapping is not only fun, but can reveal patterns that are hard to see otherwise. The chestnut project showed what we’d always known based on casual observation, that the trees are concentrated on the ridgetops, but I was surprised at just how many grow on the lower slopes. And they clearly avoid the less acidic soil of the Juniata Formation in favor of its flanking Bald Eagle and Tuscarora formations. The relative few in the latter, on Sapsucker Ridge, either grow among the dense blueberry and huckleberry bushes flanking the open rock slopes—which provide plenty of sunlight for flowering—or on steep slopes, where deer don’t browse as much as on the ridgetop. Laurel Ridge, by contrast, has a much denser understory to protect the sprouts until they get past deer browse height (5-6 feet).

In any case, keeping the deer numbers as low as possible seems key to their long-term survival, so best of luck to all the hunters out there.